Earliest true hardware

Devices have been used to aid computation for thousands of years, mostly using one-to-one correspondence with our fingers. The earliest counting device was probably a form of tally stick. Later record keeping aids throughout the Fertile Crescent included calculi (clay spheres, cones, etc.) which represented counts of items, probably livestock or grains, sealed in containers.[1][2] The use of counting rods is one example.The abacus was early used for arithmetic tasks. What we now call the Roman abacus was used in Babylonia as early as 2400 BC. Since then, many other forms of reckoning boards or tables have been invented. In a medieval European counting house, a checkered cloth would be placed on a table, and markers moved around on it according to certain rules, as an aid to calculating sums of money.

Several analog computers were constructed in ancient and medieval times to perform astronomical calculations. These include the Antikythera mechanism and the astrolabe from ancient Greece (c. 150–100 BC), which are generally regarded as the earliest known mechanical analog computers.[3] Hero of Alexandria (c. 10–70 AD) made many complex mechanical devices including automata and a programmable cart.[4] Other early versions of mechanical devices used to perform one or another type of calculations include the planisphere and other mechanical computing devices invented by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (c. AD 1000); the equatorium and universal latitude-independent astrolabe by Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī (c. AD 1015); the astronomical analog computers of other medieval Muslim astronomers and engineers; and the astronomical clock tower of Su Song (c. AD 1090) during the Song Dynasty.

Suanpan (the number represented on this abacus is 6,302,715,408)

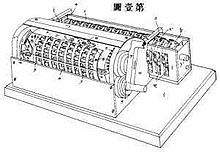

Yazu Arithmometer. Patented in Japan in 1903. Note the lever for turning the gears of the calculator.

In 1642, while still a teenager, Blaise Pascal started some pioneering work on calculating machines and after three years of effort and 50 prototypes[9] he invented the mechanical calculator.[10][11] He built twenty of these machines (called the Pascaline) in the following ten years.[12]

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz invented the Stepped Reckoner and his famous cylinders around 1672 while adding direct multiplication and division to the Pascaline. Leibniz once said "It is unworthy of excellent men to lose hours like slaves in the labour of calculation which could safely be relegated to anyone else if machines were used."[13]

Around 1820, Charles Xavier Thomas created the first successful, mass-produced mechanical calculator, the Thomas Arithmometer, that could add, subtract, multiply, and divide.[14] It was mainly based on Leibniz' work. Mechanical calculators, like the base-ten addiator, the comptometer, the Monroe, the Curta and the Addo-X remained in use until the 1970s. Leibniz also described the binary numeral system,[15] a central ingredient of all modern computers. However, up to the 1940s, many subsequent designs (including Charles Babbage's machines of the 1822 and even ENIAC of 1945) were based on the decimal system;[16] ENIAC's ring counters emulated the operation of the digit wheels of a mechanical adding machine.

In Japan, Ryōichi Yazu patented a mechanical calculator called the Yazu Arithmometer in 1903. It consisted of a single cylinder and 22 gears, and employed the mixed base-2 and base-5 number system familiar to users to the soroban (Japanese abacus). Carry and end of calculation were determined automatically.[17] More than 200 units were sold, mainly to government agencies such as the Ministry of War and agricultural experiment stations.[18][19]

[edit] 1801: punched card technology

- Main article: Analytical engine. See also: Logic piano

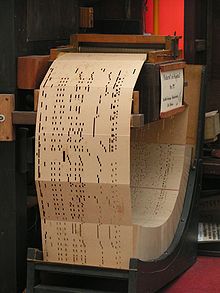

Punched card system of a music machine, also referred to as Book music

In 1833, Charles Babbage moved on from developing his difference engine (for navigational calculations) to a general purpose design, the Analytical Engine, which drew directly on Jacquard's punched cards for its program storage.[20] In 1837, Babbage described his analytical engine. It was a general-purpose programmable computer, employing punch cards for input and a steam engine for power, using the positions of gears and shafts to represent numbers. His initial idea was to use punch-cards to control a machine that could calculate and print logarithmic tables with huge precision (a special purpose machine). Babbage's idea soon developed into a general-purpose programmable computer. While his design was sound and the plans were probably correct, or at least debuggable, the project was slowed by various problems including disputes with the chief machinist building parts for it. Babbage was a difficult man to work with and argued with everyone. All the parts for his machine had to be made by hand. Small errors in each item might sometimes sum to cause large discrepancies. In a machine with thousands of parts, which required these parts to be much better than the usual tolerances needed at the time, this was a major problem. The project dissolved in disputes with the artisan who built parts and ended with the decision of the British Government to cease funding. Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron's daughter, translated and added notes to the "Sketch of the Analytical Engine" by Federico Luigi, Conte Menabrea. This appears to be the first published description of programming.[21]

IBM 407 Accounting Machine (tabulator)

A machine based on Babbage's difference engine was built in 1843 by Per Georg Scheutz and his son Edward. An improved Scheutzian calculation engine was sold to the British government and a later model was sold to the American government and these were used successfully in the production of logarithmic tables.[22][23]

Following Babbage, although unaware of his earlier work, was Percy Ludgate, an accountant from Dublin, Ireland. He independently designed a programmable mechanical computer, which he described in a work that was published in 1909.

In the late 1880s, the American Herman Hollerith invented data storage on a medium that could then be read by a machine. Prior uses of machine readable media had been for control (automatons such as piano rolls or looms), not data. "After some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards..."[24] Hollerith came to use punched cards after observing how railroad conductors encoded personal characteristics of each passenger with punches on their tickets. To process these punched cards he invented the tabulator, and the key punch machine. These three inventions were the foundation of the modern information processing industry. His machines used mechanical relays (and solenoids) to increment mechanical counters. Hollerith's method was used in the 1890 United States Census and the completed results were "... finished months ahead of schedule and far under budget".[25] Indeed years faster than the prior census had required. Hollerith's company eventually became the core of IBM. IBM developed punch card technology into a powerful tool for business data-processing and produced an extensive line of unit record equipment. By 1950, the IBM card had become ubiquitous in industry and government. The warning printed on most cards intended for circulation as documents (checks, for example), "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate," became a catch phrase for the post-World War II era.[26]

Punched card with the extended alphabet

Computer programming in the punch card era was centered in the "computer center". Computer users, for example science and engineering students at universities, would submit their programming assignments to their local computer center in the form of a deck of punched cards, one card per program line. They then had to wait for the program to be read in, queued for processing, compiled, and executed. In due course, a printout of any results, marked with the submitter's identification, would be placed in an output tray, typically in the computer center lobby. In many cases these results would be only a series of error messages, requiring yet another edit-punch-compile-run cycle.[29] Punched cards are still used and manufactured to this day, and their distinctive dimensions (and 80-column capacity) can still be recognized in forms, records, and programs around the world. They are the size of American paper currency in Hollerith's time, a choice he made because there was already equipment available to handle bills.

[edit] Desktop calculators

Main article: Calculator

The Curta calculator can also do multiplication and division

Companies like Friden, Marchant Calculator and Monroe made desktop mechanical calculators from the 1930s that could add, subtract, multiply and divide. During the Manhattan project, future Nobel laureate Richard Feynman was the supervisor of the roomful of human computers, many of them female mathematicians, who understood the use of differential equations which were being solved for the war effort.

In 1948, the Curta was introduced. This was a small, portable, mechanical calculator that was about the size of a pepper grinder. Over time, during the 1950s and 1960s a variety of different brands of mechanical calculators appeared on the market. The first all-electronic desktop calculator was the British ANITA Mk.VII, which used a Nixie tube display and 177 subminiature thyratron tubes. In June 1963, Friden introduced the four-function EC-130. It had an all-transistor design, 13-digit capacity on a 5-inch (130 mm) CRT, and introduced Reverse Polish notation (RPN) to the calculator market at a price of $2200. The EC-132 model added square root and reciprocal functions. In 1965, Wang Laboratories produced the LOCI-2, a 10-digit transistorized desktop calculator that used a Nixie tube display and could compute logarithms.

In the early days of binary vacuum-tube computers, their reliability was poor enough to justify marketing a mechanical octal version ("Binary Octal") of the Marchant desktop calculator. It was intended to check and verify calculation results of such computers.

[edit] Advanced analog computers

Main article: analog computer

Before World War II, mechanical and electrical analog computers were considered the "state of the art", and many thought they were the future of computing. Analog computers take advantage of the strong similarities between the mathematics of small-scale properties—the position and motion of wheels or the voltage and current of electronic components—and the mathematics of other physical phenomena, for example, ballistic trajectories, inertia, resonance, energy transfer, momentum, and so forth. They model physical phenomena with electrical voltages and currents[31] as the analog quantities.Centrally, these analog systems work by creating electrical analogs of other systems, allowing users to predict behavior of the systems of interest by observing the electrical analogs.[32] The most useful of the analogies was the way the small-scale behavior could be represented with integral and differential equations, and could be thus used to solve those equations. An ingenious example of such a machine, using water as the analog quantity, was the water integrator built in 1928; an electrical example is the Mallock machine built in 1941. A planimeter is a device which does integrals, using distance as the analog quantity. Unlike modern digital computers, analog computers are not very flexible, and need to be rewired manually to switch them from working on one problem to another. Analog computers had an advantage over early digital computers in that they could be used to solve complex problems using behavioral analogues while the earliest attempts at digital computers were quite limited.

Some of the most widely deployed analog computers included devices for aiming weapons, such as the Norden bombsight,[33] and fire-control systems,[34] such as Arthur Pollen's Argo system for naval vessels. Some stayed in use for decades after World War II; the Mark I Fire Control Computer was deployed by the United States Navy on a variety of ships from destroyers to battleships. Other analog computers included the Heathkit EC-1, and the hydraulic MONIAC Computer which modeled econometric flows.[35]

The art of mechanical analog computing reached its zenith with the differential analyzer,[36] built by H. L. Hazen and Vannevar Bush at MIT starting in 1927, which in turn built on the mechanical integrators invented in 1876 by James Thomson and the torque amplifiers invented by H. W. Nieman. A dozen of these devices were built before their obsolescence was obvious; the most powerful was constructed at the University of Pennsylvania's Moore School of Electrical Engineering, where the ENIAC was built. Digital electronic computers like the ENIAC spelled the end for most analog computing machines, but hybrid analog computers, controlled by digital electronics, remained in substantial use into the 1950s and 1960s, and later in some specialized applications.

Walang komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento